The Agreement on International Humane Trapping Standards (AIHTS) is an attempt to establish and enforce an international standard on humaneness for traps. It’s likely to be implemented in the UK in the near future, so here is what you need to know.

The Agreement on International Humane Trapping Standards (AIHTS) is an attempt to establish and enforce an international standard on humaneness for traps. It’s likely to be implemented in the UK in the near future, so here is what you need to know.

[Updated 15 February 2018]

- What is AIHTS?

- What does AIHTS mean for gamekeepers?

- Are Fenn traps going to be made illegal?

- Is the UK obliged to implement AIHTS?

- Why didn’t we get more warning?

- How did the UK reach the current predicament?

- What is Defra’s proposal for implementation of AIHTS?

- What is the UK situation as of January 2018?

- What if I need to buy traps right now?

What is AIHTS?

The agreement was brokered in 1997 to resolve a trade embargo threatened by the EU in 1991 against countries that traded fur from wild animals caught by inhumane methods. The dispute had begun with pressure inside the EU from animal rights groups protesting against fur trade, focused particularly on the use of leg-hold traps. This backfired to some extent because fur-trading nations pointed out that similar traps were commonly used in EU countries to catch the same species (e.g. muskrat, coypu) or similar species as pests, and that no humaneness standards were applied there. Because fur trading was economically important — particularly for Canada and Russia, but also for some EU countries like Denmark and Iceland — and because pest control was also critical, a compromise was thrashed out: the AIHTS. This requires signatory countries to prohibit traps for fur-bearing species that will not pass a clearly specified humaneness test.

The AIHTS humaneness test was derived from discussions towards an international standard on humaneness in traps, a process which had been derailed by animal rights lobbyists within the technical working group, who ultimately asserted that no trap could ever be considered humane. The ISO standard salvaged from those failed discussions defined how to test traps but stopped short of defining a threshold for acceptability. An acceptability standard was defined in AIHTS. This reflects performance of the better traps available, but is nevertheless realistic.

AIHTS applies only to a list of species commonly caught in the wild for their fur. Of these, only otter, beaver, marten, badger and stoat occur in the UK, and under current UK law only stoat may be taken or killed without special licence. Notably missing from the AIHTS list are mink and fox. This is because fur from those species is mostly taken from fur farm stock, to ensure consistency, and to use variants that are rare in the wild. Weasel is also not listed: this is because it is not caught as a furbearer.

The AIHTS standard is not fixed, and it was anticipated that both the humaneness criteria and the list of species to which AIHTS applied would evolve in time.

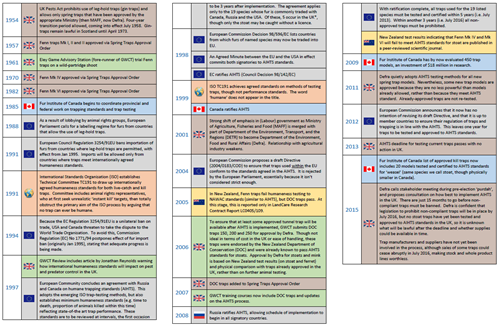

A timeline for the evolution of AIHTS and its implementation by signatory countries can be found here.

What does AIHTS mean for gamekeepers?

There will be changes to the list of traps that are approved to catch stoats. From what we already know about trap performance, the Fenn Mk 4 and Mk 6 traps (and copycat designs), and all the BMI Magnum traps fail the AIHTS standard. These probably account for 90% or more of all traps currently used as tunnel traps in the UK.

So the main likely consequences of AIHTS are:

- Cost of replacement traps

- Modification of tunnels to suit replacement traps

- Cost of deployment in the field

- It will probably be necessary for rat and squirrel control to become separate exercises using pre-baiting, appropriate baits, in more intensive campaigns focused on specific locations. Stoats and weasels can then be targeted using traps approved for them, with suitably restricted entrances to the tunnels.

Some other traps currently approved for stoat have not been tested to AIHTS standard, and are unlikely to be tested because of lack of interest from the manufacturer or the user community. These include the WCS tube trap.

Are Fenn traps going to be made illegal?

Fenn traps, and all copycat designs such as those by Springer and Solway, will be made illegal to catch stoats, because tests have shown that they fail to kill stoats reliably within the time-frame required by AIHTS (45 seconds). We do not yet know whether Defra will continue to allow their use to catch other target species for which they are currently approved (e.g. weasels, rats, squirrels). That decision will not be made until after a public consultation expected to be launched in January 2018. The AIHTS does not apply to those other species, and few traps have undergone humaneness testing for them, because of cost constraints.

Is the UK obliged to implement AIHTS?

The AIHTS is binding on all EU member states, and Defra has indicated that the UK will remain committed to it after Brexit. Morally, a commitment to raise humaneness standards in wildlife management is unarguable, provided it doesn’t render management ineffectual or prohibitively expensive. We do, however, have concerns about its implementation, which we will voice in our response to the public consultation.

Why didn’t we get more warning?

The AIHTS allowed an eight-year period for implementation, from the moment the agreement was signed in 2008. Most of this was squandered through protracted negotiations and indecision within the EU and lack of preparedness at member-state level. As far as we know, only Sweden, Finland, Slovakia and possibly Hungary were already compliant with AIHTS by the July 2016 deadline. See the next section for more detail about the UK specifically.

Because few fur-bearing species addressed by AIHTS are trapped in the UK, the UK was largely compliant by July 2016, with stoats the principle outstanding issue. The problem with stoats was that no trap had been found that made a satisfactory substitute for Fenn traps from a practitioner’s point of view. The UK therefore argued that it needed extra time to facilitate changes.

How did the UK reach the current predicament?

Following completion of signatures to the AIHTS in 2008, a period of five years was allowed for trap testing to take place, followed by three years for trap users to make any necessary changes to their practices. The total eight-year transition expired at the end of July 2016. The GWCT began warning about the implications of AIHTS for predator and pest management in 1997, with an article in the Review, but the UK was slow to implement AIHTS. In part, this was because, for four years after ratification, the EU was apparently working towards a Directive on the matter. The EU dropped that ambition in 2012, arguing that member countries should in any case be implementing the agreement in their domestic law. That still left four years before implementation had to be complete.

In the UK, Defra is the government department responsible for regulation of spring traps (Pests Act 1954). All spring traps must be approved by Defra, although there has not previously been any published standard they must conform to for approval. In 2012, Defra stated that future new trap approvals would be granted only to traps that pass the AIHTS standard, irrespective of species. They even extended this scrutiny to fox snares, which did not fall under either the Pests Act (because a snare is not a spring trap) or AIHTS (because fox is not one of the species it covers).

Defra finally got to grips with implementation of AIHTS in spring 2015, leaving only 15 months of the original eight years to complete trap testing, amend legislation relating to traps, inform the trap-using community of changes to trap approvals, and for the ‘industry’ (manufacturers, importers, retailers, users) to effect those changes. In spring 2015, Defra held discussions with organisations (including the GWCT) associated with shooting and pest control, and with UK trap manufacturers/retailers, to clarify the options for trap testing and trap approvals. Defra expected to progress to a public consultation on the matter by the end of September 2015, but this was deferred pending further developments. When the deadline of July 2016 passed, no suitable substitutes for failed stoat traps had been identified.

Subsequently, however, Defra set up a Technical Working Group with members from organisations representing all the major practitioner groups (including the GWCT). This group oversees the use of a fund to cover the cost of humaneness-testing for promising candidate traps. 50% of the fund was put up by Defra; 50% by the other members of the group. It is expected to be sufficient to see a handful of models through to approval. Trap-testing progress has been slow, chiefly because of a shortage of suitable candidate traps that are developed to a point where they could be manufactured in quantity.

Defra has proposed that in future, those who submit new traps for approval (i.e. manufacturers/importers/retailers) will have to bear the (substantial) cost of trap testing.

What is Defra’s proposal for implementation of AIHTS?

Defra’s proposals will be revealed in a public consultation expected to be launched in late February 2018. It proposes that the use of traps that have failed the AIHTS for stoat will now be withdrawn on 31 December 2018. The consultation documents will detail what alternative traps will be approved for stoats by that date.

We understand that Defra will propose to implement AIHTS by moving stoat to Schedule 6 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act. This would make stoat a protected species, but there would then be a General Licence allowing it to be caught using specific trap types detailed in a Spring Traps Approval Order.

Defra’s final policy decision will be influenced by the outcome of the public consultation. Although the GWCT will of course respond to the consultation, individuals from all sectors (gamekeepers, landowners, pest controllers, trap manufacturers) are also encouraged to respond. A major concern will be the desperately short period allowed for outgoing traps to be replaced, particularly considering the modest production capacity of the trap-manufacturing companies. We will include a link to the consultation on this web page when it is announced.

What is the UK situation as of January 2018?

We understand that approval for stoat will be withdrawn from the following traps:

- Fenn Mk 4 and Mk 6 and copies thereof (e.g. Springer 4 and 6; Solway Mk 4 and Mk 6)

- BMI Magnum 55, 110 and 116

- WCS tube trap

As well as a few ‘legacy’ models (e.g. Juby, Imbra) that are no longer manufactured. Subject to conclusions of the public consultation, approval of these traps for other species will be unchanged, but wherever there was a risk of catching a stoat you would have to use a trap approved for stoats.

Approval for stoat will be continued for:

- DOC 150

- Goodnature A24

The list of traps approved for stoat will be supplemented further by the time the AIHTS is implemented, but Defra has not yet announced the details. Watch this page for further news.

What if I need to buy traps right now?

If you are considering buying traps for use in 2018, you currently have four options:

- Option 1: Don’t buy anything until it’s all a lot clearer. Cheapest and safest, but if you are short of traps for spring/summer 2018, may not be a real option.

- Option 2: If you want to do untargeted tunnel trapping where there’s a likelihood of catching stoats, and really don’t mind if they become redundant at the end of 2018, Fenn Mk 4s are the cheapest option. But at some time in the near future (probably 1 January 2019, but this is not yet absolute) these will definitely become unlawful for stoats.

- Option 3: If you want to do untargeted tunnel trapping where there’s a likelihood of catching stoats, and you want the traps to be useable beyond 2018, you’d have to go for DOC 150s, because these are the only future-proof brand that’s already legal and compatible with existing tunnels. During 2018, you’d have to use these in the currently prescribed (single-entry) tunnel design, although it’s likely that Defra will relax this restriction later. DOC 150s are a more expensive option than Fenn Mk 4s, and by making this investment now, you miss the chance to consider other trap designs that will be approved during 2018/19.

Option 4: In England only, if you want to be adventurous, you could go for Goodnature A24s, which are not a tunnel trap but are self-emptying and self-resetting, and therefore need less frequent maintenance visits than other traps. Efficacy in UK conditions is unproven, but their use in attempted stoat eradication in New Zealand is well documented on the manufacturer’s website. A24s are relatively expensive, require a radically different approach, and depend on the use of a long-life scent lure.

Option 4: In England only, if you want to be adventurous, you could go for Goodnature A24s, which are not a tunnel trap but are self-emptying and self-resetting, and therefore need less frequent maintenance visits than other traps. Efficacy in UK conditions is unproven, but their use in attempted stoat eradication in New Zealand is well documented on the manufacturer’s website. A24s are relatively expensive, require a radically different approach, and depend on the use of a long-life scent lure.

Unfortunately, the manufacturer’s stoat lure is not yet available in the UK, although we understand that plans are afoot to remedy that. Also, A24s are coloured orange and black, which is not ideal where the public might interfere with traps. Finally, in New Zealand these traps are approved as humane to kill hedgehogs, which are an introduced pest in New Zealand, but a protected native species in the UK. To be right side of UK law, you must take precautions to exclude hedgehogs and other Schedule 6 species from A24s. The UK importer sells an add-on hedgehog excluder. Goodnature A24s are not currently authorised for use in Wales, Scotland or Northern Ireland.

Credit for Article to Game & Wildlife Cconservation Trust - https://www.gwct.org.uk/